Uneasy Money

In the first of a series on the ways arts are funded in Aotearoa, we journey into the world of philanthropy and ask: does money still flow from the mansion on the hill?

THERE'S A BEND where the gate meets the road. The bronze sign carrying the surname of two well-known New Zealand philanthropists goes unseen to passing cars. “GIBBS FARM IS A PRIVATE PROPERTY.” When I press the intercom, static fills the small box and no voice emerges. I wait pensively, hoping that someone will hear my call.

I had tried in vain to make an appointment to enter the farm, but the gates are well and truly shut and the treasures within more secluded than ever. I had also asked to interview Jenny Gibbs, the lady of the Gibbs family — nay, the dame, after she was honoured for ‘services to the arts’ in 2009. Since she and Alan Gibbs separated in the mid-1990s, she has lived in Auckland while Alan moved between his London base and the Kaipara farm. We had a brief correspondence over email. Dame Jenny, a history-lecturer-turned-millionaire-art-philanthropist, didn’t like the sound of the article I was wanting to interview her for — especially the name. Being unable to land an interview was an apt start to proceedings.

Still, I always knew that the farm would be my first physical stop — it’s a landmark symbol of art philanthropy in Aotearoa. Staring over the fence at Alan Gibbs’ sculpture park, like waiting in vain for a reply from Dame Jenny, offered clear metaphors for the inaccessible wealth that I was afraid I’d find.

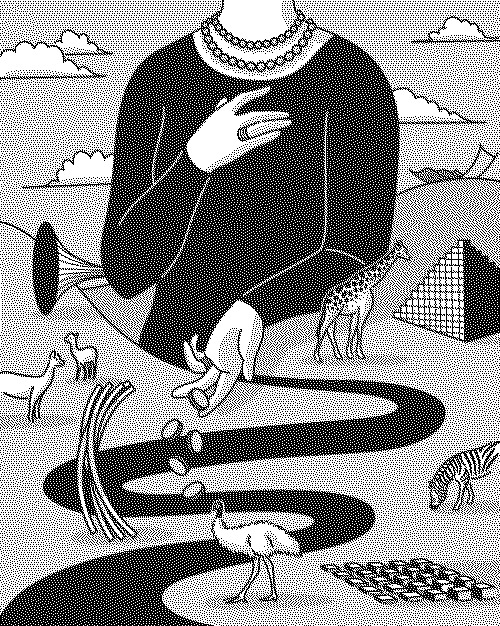

I used to give guided tours of the farm to patrons of Auckland Art Gallery. The enormous sculptural commissions didn’t interest me much, but I liked the animals. Gibbs had populated the Kaipara landscape with creatures of the savannah and Serengeti, a surreal addition to the native bird calls that drifted into the vast PVC membrane of Anish Kapoor’s Dismemberment, Site 1 (2009). But I never got to see the replica Western town hidden on the grounds, or the fabled Gibbs Aquada, an aquatic-tank-slash-sports-car developed by Alan Gibbs in the 1990s.

The promotional video for the Aquada is easier to access on YouTube. The drive begins on the open road with Prodigy’s ‘Firestarter’ before transitioning to the majestic xylophones of Hans Zimmer — cue water and the arrival of the Aquada. The driver smiles, then laughs, then howls with delirious joy. I like to think this is how Alan Gibbs felt when he and his business partner, Trevor Farmer, sold their shares in the newly privatised Telecom for over $300 million throughout the 1990s.

Gibbs Farm is a ‘mansion on the hill’ in Aotearoa, and many artists have entered those gates looking for money to realise their art. Over two decades, Alan Gibbs commissioned and had erected improbable monoliths by local and international artists on 400 hectares of expansive hills overlooking the Kaipara. Back in town in her art-gallery-like mansion on Paritai Drive, Jenny Gibbs became a civic empress of the arts during a boom period for contemporary work in the late 1990s and 2000s. Separately yet together, they made the name ‘Gibbs’ chime like Medici in these islands. A great deal of this money for the arts came from the neoliberal finance coup of the late 20th century, the privatisation of state-owned assets — a fact that many instinctively left-leaning artists might prefer to ignore.

It’s uneasy money, though, and we’re caught in a dilemma.

RICH PEOPLE — especially rich people connected to the rule of the state — have long been principal funders of the arts. It’s been that way for thousands of years, especially in the European world from which the structures of our colonial state emerged. The artistic patronage of religious, civic and aristocratic authorities held sway before the existence of modern democracy and capitalism and, with them, the rise of a new preeminent figure of wealth, the business-man. The new industrialists with their unprecedented wealth could buy whatever they wanted — everything except the respect of the people who worked for them or whom their political allies ostensibly governed. Cue philanthropy and the civic businessman. This archetype of giving seems enshrined in the very names of legendary family dynasties: the Rothschilds, the Rockefellers and, closer to home, our very own family-givers, the Friedlanders, the Todds, and, yes, Dame Jenny and Alan Gibbs.

In Aotearoa, philanthropic giving — big and small — amounts to around $4 billion each year (or approximately 1.1% of GDP). In the scheme of things, it’s not that much, and only 2.5% (or around $40 million) is put towards the arts each year. What does go to the arts generally goes to the fine arts, a field of especially dramatic cultural capital in the creative economy. Art and money have long fed off one another: one for subsistence, the other for prestige. This usually happens out of sight. The wealthy people at the heart of our philanthropy are hesitant to talk to the media, and not all donor names are disclosed. But there’s one place where you can see it clearly: the ‘Honour Wall’ of Auckland Art Gallery, where the rich and powerful of Aotearoa are writ large in valorising steel. Big names on big buildings, that’s the orthodoxy.

Something is changing, though, and amid exhibition openings and private dinners, rumours are coursing their way through the art world. The baby-boomer mansions that we have long relied on are closing their gates and everyone wants to know where the money will come from next. There appear fewer Gen Xers and millennials able to take their place and, perhaps more concerning, a changing attitude towards wealth, to one less vested in civic demonstrations of generosity.

I wanted to know if money still flowed from the mansion on the hill. Who are the people — if any — sustaining our arts?

“‘PATRON’ IS NOT A WORD that entices a lot of young New Zealanders,” says Jo Blair, the director of Brown Bread, a specialist art philanthropy consultancy based in Ōtautahi Christchurch, who has accrued a reputation as someone who can transform financial futures for creatives. “Americans and Australians want to put their hand up at a fundraiser and receive the attention; they love that. We’re more shy. More like the British — polite, under the radar, not frivolous.” True enough. Wealthy New Zealanders prefer to style themselves discreetly in ‘Kiwi’ culture, assuming unassuming ways.

Blair is part of a professional class that has grown up around charities (a sector that employs roughly 5% of working New Zealanders), and she can eloquently deliver the pitch: “Brown Bread believes that philanthropy is more about driving a movement and creating change rather than just fundraising. It’s actually a much bigger project of cultural change.” She has helped orchestrate some of the biggest recent movements in philanthropic giving to the arts, including the establishment of a significant endowment for Christchurch Art Gallery. And change is needed here. According to a recent Creative New Zealand report, nearly six out of 10 New Zealanders have a relatively ambivalent attitude towards the arts. It must be hard to make the case for giving in the arts, when more than half of people don’t think they’re especially important.

Blair has advised the Arts Foundation, our most heavily endowed and comprehensive arts trust, for over a decade and knows the history of her field. She tells the story of how the Arts Foundation was founded in the late 90s — by “superheroes”, people who helped catalyse modern philanthropy in New Zealand, building on the significant gifts of building and collections in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But things have been changing recently for the foundation and its wealthy patrons. “In the 1980s and 90s, when there was good interest [rates] and surpluses of funds, arts organisations used to be able to run off their endowments,” Blair remembers. But interest rates have been low for more than a decade now (though now rising again) and endowments have had to rethink their financial models to continue their work. It’s been a tough transition. As Blair explains, “All the people who have carved the path are saying, ‘Let’s get a new generation in’.”

The master fundraiser has come to realise that that’s easier said than done. “It’s challenging because there are so many more [charitable] offerings now,” she says. “Everyone has their philanthropic programmes established.” It’s a competitive market out there, for giving most of all. There are people in poverty, an ecosystem in crisis, sick and endangered animals, each making a compelling case for donations. “The arts are often seen at the bottom of the list because they are not seen as critical. They are not serving the bottom of the cliff doing immediate saving or relief for humanity,” explains Blair. This grim prioritisation is aligned with ideas of ‘effective altruism’ that have been in the ascendant recently. Effective altruism is a philosophy of giving that prompts prospective donors to ask: ‘How can I best — and most efficiently — help others?’ Unsurprisingly, the arts don’t perform well in the race to save lives; their value is more ethereal and harder to locate on the spreadsheet. The arts may attest to the life worth living, but they’re not generally in the business of saving it.

There are other issues, too. Referring to research conducted by Brown Bread, Blair notes that potential donors “want to see how supporting the arts will make New Zealand better”. “The overwhelming theme among high-net-worth 40- to 50-year-olds”, she says, “was, ‘We really want to give to the arts, but we’re quite intimidated by them’.” This may seem a reasonable point to anyone who’s attended an art opening, but the change is decisive. The art world used to rely on elitism, selling itself as exclusive, and money was a relatively straightforward way to get in. With the alliance between money and art more tense these days, Blair’s job is anything but simple. “There can be a bit of fear. The artists can be scared of wealthy people, and wealthy people are often intimidated by the artists — so how do we bring us all together?” How indeed. I think of the rise of decolonial, anti-capitalist, sometimes downright revolutionary art practices in the past decade and imagine they might be a tough sell to the hedge fund managers.

THE SUMMER RAIN LASHES the facade of Commercial Bay. I needed to go where the new money was and the 41 lit-up storeys of PwC Tower are like a beacon. Little Queen Street feels like a good place to look for the next generation of wealth, and sitting in a Korean restaurant overlooking our financial hub, I wonder if any of these suited professionals have plans to give to the arts.

Harry Cundy arrives in casual corporate attire and orders a bottle of rosé for the conversation ahead. He starts with a disclaimer: “I’m a bit of a shit fundraiser. I get quite awkward and embarrassed asking people for money.” I begin to wonder if I am sitting with the wrong corporate representative, and remind myself of Cundy’s unique experience. A junior partner at the dealer gallery Hopkinson Cundy (which became Hopkinson Mossman, and then just Mossman before closing in late 2020), Cundy has also served on the board of Artspace Aotearoa. He knows a thing or two about tax and the legislative environment that enables philanthropic giving, and is currently working as a legal adviser to one of the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms.

I had hoped Cundy could help me understand the financial side of how giving works. Philanthropy is not all private parties; it’s also tax and policy. Cundy explains that our legal definition of charitable work comes from English common law, specifically around the Statute of Elizabeth of 1601. “When we talk about ‘other charitable purposes’ beneficial to the community, that is limited to things that are analogous to the preamble to that particular statute,” says Cundy, a perfectly sautéed bean in hand. “Common law always works by analogy — there are analogies on analogies on analogies.” Looking at the Elizabethan preamble, it’s curious to imagine the community benefits of art as somehow equivalent to the “relief of aged, impotent, and poor people” or, even more anachronistically, “the marriages of poor maids”. Still, amid the sometimes overblown social claims about art, Cundy knows that in his own life, “art has been good for me”.

As Cundy dresses the milk buns, he explains the basic finance of philanthropy. It’s fairly simple. Donors get a 33-cent tax credit on every dollar given (or 28 cents for companies). You also don’t have to pay tax on your income if you’re a registered charity (including interest and dividends if the charity has any savings or investments) — although your outputs must be engaged toward your charitable purpose. So far, standard enough. If you look at the international context, however, the incentives and tax benefits for charitable giving appear relatively modest in Aotearoa. The United States offers rebates of up to 60 cents on the dollar (though this incentive varies depending on the nature of the gift), but it also trusts the charity sector to solve problems in lieu of the state to an unusual degree. In Aotearoa, we are more circumspect, extending less faith to the discretionary giving of the wealthy. Ultimately, it is a societal and political question, and our policies adopt a moderate view of the philanthropic gift.

There have been calls to further incentivise philanthropic giving, including a proposal to make donations of artworks tax deductible, which could assist the movement of significant works into public collections. Cundy explains that it’s not quite that simple, and the Inland Revenue Department has reason to be cautious. “The ‘valuation of artworks’ question is real. There’s enough vested interest that you can imagine someone gifting an artwork to a public collection on the basis of them agreeing that it’s worth a million dollars.” Values on the secondary art market fluctuate dramatically, and that market is prone to insider trading. Using these values to generate tax credits could be spurious. Cundy — a lover of art and public resources — thinks something could be figured out. “There could be a halfway house in which we say, ‘Okay, you can donate your artwork, but we’ll ask you what you bought it for, and that’s what we’ll offer a tax credit for’.” Would collectors donate their million-dollar Hotere for the proverbial peanuts they bought it for? Probably not.

For Cundy, such reforms are not the urgent business before us, and there is one piece of tax reform he is keen to direct my attention to. “I think a capital gains tax should happen, for reasons of equity, if nothing else. The New Zealand tax system is becoming increasingly a mess, as Inland Revenue tries to deal with some of the issues presented by not having a capital gains tax, without being able — for political reasons — to introduce an actual capital gains tax.” The issue may seem beside the philanthropic point but it’s not, given that questions of philanthropy are ultimately also questions of wealth accumulation.

While art philanthropy is in the slumps, rich people do not lack for money. In fact, they just keep getting richer. Much richer. Asset owners in this country made an unprecedented $872 billion gain over the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, largely because of a 54% (untaxed) rise in house prices. Blair was well aware of this, too, commenting that she “might have to tweak our strategy to focus more on uber-high-net-worth individuals”. All this untaxed money raises the question: if our state could more fairly gather its portion of the nation’s wealth, maybe our arts wouldn’t have to depend on the benevolent discretion of a wealthy few?

From his time fundraising at Artspace Aotearoa, Cundy knows that the next generation of philanthropists is failing to appear, and the reason is glaringly obvious. “There’s a whole story that could be told about the New Zealand art market through the lens of the Auckland property market. There is a generational distribution of the capital gains that have accrued to property in Auckland. And that’s people at a certain age and stage of their life, and they have their own particular interests. I don’t think it’s outrageous to think that people will tend to support work and artists who are of a similar generation to them.” The neoliberal economy of the past 40 years, so powerfully leveraged by the Alan Gibbs of this world, also empowered a wider generation of landowners, through a precipitous rise in the value of property. Unsurprisingly, this generation likes their own artists best.

THE DIRECTOR OF OBJECTSPACE pours coffee in an open-plan office. Discussions of philanthropy generally don’t invite openness, but the staff of Objectspace seem relaxed with the journalist in their midst. They probably know I’ve come looking for the ‘good news’ part of the story. And fair enough — Objectspace has achieved a remarkable transformation in the seven years of Kim Paton’s leadership, the centrepiece of which has been a purpose-built gallery on Rose Rd in Ponsonby, an otherwise stale part of Auckland. Enabling it all was a transformation in the institution’s finances, going from zero philanthropy to roughly half a million in yearly contributions from donors. Objectspace’s approach to fundraising, then, is something like the fabled ‘best practice’.

Objectspace has a dynamic and multivarious programme. As Paton explains, “Making practices are absolutely at the heart of Objectspace. We’re anchored by the disciplines of craft, design and architecture — we live in that overlap.” It is the only institution in Aotearoa with such a mandate. As Jo Blair similarly commented, “Objectspace was really needed. The thing you’re trying to fund must be innovative, cutting edge and new.” Objectspace is that, and its team seems to be possessed of a relentless will to improve the institution. “We’ve never done anything that was perfect,” Paton says. It’s humility that seems recognisably of New Zealand, and makes Paton feel relatable amid the rarefied world of museum directors.

For Objectspace, building a new gallery was vital. Paton knows that “without that big capital project, it would have been much slower to build a philanthropy community”. This is the rub for fundraising in the arts — it’s easier to generate support for large, one-off projects; “what’s difficult is finding support for your electricity bill,” Paton says.

While a vision more compelling than utility bills is important, it also helps to have people skills. Paton puts it another way, “The one piece of feedback we get more than anything else is around our hosting. The amount of feedback we’ve had on that is profound. The simple act of how you care for the artists and people you work with, and your visitors, has become the foundation of our community.” People — and money — need to be wooed and reassured a little, and Objectspace has figured out the way to do it. Blair insists it’s bigger than that. Objectspace has discovered how to access elusive younger audiences and, with them, donors. “People don’t want to go to an event where there’s a bunch of old people in pearls drinking wine. However, if you can create the right atmosphere, age won’t come into it.” Instead of the wine and pearls, Objectspace tends to host croissant breakfasts and artist talks, and allows the strength of its programme to engage prospective donors.

While philanthropy has been transformational for the gallery, Paton is clear on what is required to sustain an institution like Objectspace. “I don’t believe there’s any viable, sustainable model other than a public–private mix. What we need is more reliable, more sustainable and greatly enlarged sources of public funding, to limit the demands on private sources.” The robust combination of public funds and private philanthropy at Objectspace attests to a basic fact — money begets money. Philanthropists don’t want to be singularly holding the purse strings and, when public funds are threatened, so is the stability of private contributions. It is this feedback loop that has made the current threatened cuts to local arts funding in Auckland under the new mayor’s proposed budget so alarming. While the contribution of Auckland Council to an organisation like Objectspace may not seem significant, it is an essential part of a delicate ecosystem that includes private philanthropy.

For Objectspace, there is one philanthropic partnership that is sustaining above all else — with Ockham Residential, one of the country’s largest property developers. It is unusual for an institution of Objectspace’s scale to enjoy the committed support of a large corporation, and Ockham appears to be that rare thing: new money with an eagerness to support the arts in a sustained way.

Benjamin Preston — Aucklander, mathematician, teacher, bluegrass enthusiast and father of two — is one half of Ockham’s founding duo. I meet up with him at one of the ‘creative precincts’ established by the Ockham Collective, the dedicated charitable arm of Ockham. Preston confesses early in our conversation that, unlike his business partner, Mark Todd, he has “no building acumen. In fact, I struggle to change a lightbulb.” What he does not struggle with is finance. After studying mathematics and economics at the University of Auckland, Preston moved, via roles in Sydney, Johannesburg and London, to the United States to work in energy transfers in Texas.

By his late 30s, he was in a position to think about what he really wanted to do. He retrained as a school teacher and, with his childhood friend Mark, began contemplating the foundation of “a secular Dilworth’’ back home. The school never eventuated, but Ockham did. Founded in 2008, it swiftly became one of Tāmaki Makaurau’s biggest builders of medium- and high-density housing situated on transport arteries — important work in a city paralysed by a cartel of villa owners.

In this economy, with the value of New Zealand’s housing stock now four times GDP and prices that have more than doubled in many regions over the past decade, it’s no surprise that Ockham has done well. And they’re not the only ones. Surveying the list of the 100 wealthiest New Zealanders, there is a notable concentration of figures from two sectors: property and supermarkets — neither of which will surprise financially beleaguered New Zealanders. Unlike many of his wealthy peers, Preston is candid in his assessment of the situation. “One of the biggest challenges that we have in New Zealand is the dislocation of the property market from the rest of the economy. It’s almost like a false economy of its own” — savvy words to a journalist who also happens to be a landless millennial.

Ockham’s emergence seems hopeful in an industry notorious for poor behaviour. Not only in the quality of their construction and commitment to KiwiBuild, but through their ongoing contribution to the arts. For Preston, the motivation to give is simple. “I think it basically comes down to being able to share your good fortune. We have a deep belief that society benefits from public discourse, from folks getting together from being challenged in a safe way.” Explaining this, clad in a plaid shirt, Preston looks very much the Grey Lynn intellectual. Still, the commitment to ‘safe challenge’ is borne out in what Ockham chooses to fund, preferring public programming and discourse-generating platforms to the large ‘vanity’ commissions of their wealthy predecessors. According to Blair, this shift reflects a broader direction of travel in arts philanthropy. “Twenty years ago, the emphasis was on rewarding the best, and this garnered a kind of elitism. Now there is more of a desire for social engagement and evidence of the impact of the arts to society among younger donors.”

While they may not be building monuments to their wealth, associating with channels of discourse does have its own cachet. Ockham also sponsors the New Zealand Book Awards (formerly supported by Wattie’s, wine brand Montana and New Zealand Post) and funds a nonfiction series at Bridget Williams Books, the most politically progressive publishing house in the country. These disbursements seem both responsible and engaged while also enabling Ockham to wear, perhaps, a deliberate cloak of leftism that may change how we view the company’s wealth. I wonder if Ockham wants to be perceived as an ‘outsider’ to the elite, while occupying a secure place within that echelon.

I ask about The Greenhouse, Ockham’s new luxury apartment complex a stone’s throw from Objectspace that includes a $4.5 million penthouse. Surely this is the last thing the gentrified inner-city suburb needs. Is Ockham’s support of the local arts institution just an act of public relations or art-washing? Preston sees my question coming. “The one thing that Greenhouse is not is a KiwiBuild project, and doesn’t pretend to be. And like all other major cities in the world, you have to cater for all sorts of people.” Reflecting on the sometimes hazardous attention that attaches to acts of philanthropy, Preston figures that “you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t”. Going deeper, he shares his own family’s history in the contested neighbourhood. “My grandmother arrived in Auckland as a teenager from Tonga and lived in Grey Lynn in a house with 14 others. You could argue that Objectspace is the furthest thing from redressing that balance of what Grey Lynn used to represent.”

In the end, Preston was the only millionaire willing to talk to me, and his insights on wealth and society took a surprisingly philosophical turn. “Capitalism at its zenith has to retire wealth and get wealth out of the system. Otherwise, it ceases to have a reason to keep going. Basically, [rich people have] got to find a way to retire that retirement money — so they can start again.” It seems simple. If you’re really good at making money, you need to give it away so you have the motivation to make more. Preston’s words felt almost un-proprietorial; certainly his attitude of ambition and abandonment was worlds away from my own three-digit savings account and assetless portfolio.

Words from Harry Cundy came to mind: “I would be dubious of anyone who makes a strong moral claim to the money they make. Fundamentally, it is the organisation of the state as it is that allows us to make money in the way that we do.” Or, more poignantly, a recent statement by economics commentator Bernard Hickey — that the wealth he accrued by means other than his labour “was not earned and I should not fight to keep it”. In its better moments, philanthropy expresses a desire to return something from which it came.

PHILANTHROPY CAN ALSO BE downright evil. There have been dramatic examples of this internationally, most notably the Sackler family, which Preston refers to as “the House of Pain”. The Sacklers held civic prominence as generous donors to the arts while making billions selling prescription pain medication and thus contributing to an opioid epidemic that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans since 2000. This is art-washing, Preston agrees, saying that the source of philanthropic giving should be interrogated. “If you associate charitable purpose with high morals or morality, [immoral people] shouldn’t be able to feed from that trough.”

Closer to home, Ema Tavola has seen the big money that feeds from the arts trough in an effort to launder itself. The curator of gallery and community space Vunilagi Vou, Tavola is a regular speaker at Pacific and indigenous arts conferences, such as the Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art in Australia, where the principal sponsor is the mining company BHP. Tavola says of Tarnanthi that “the funders have absolutely decimated [parts of] Australia. The budget is obscene. It’s an obscene amount of money, and they engage an incredible indigenous creative director that stimulates phenomenal amounts of new work and dialogue. Everything about that festival can critique them, can critique the power of their capitalism, and the environmental decimation that they’re part of, but it still brings them capital.” Amid the contested politics of our larger neighbour, BHP’s philanthropic work “ticks a really big fucking box, a box the size of a quarry”.

The latest iteration of Vunilagi Vou rests atop a concrete island in the Tāmaki River basin, where pūkeko scamper at the edges of light industry. On the other side of the wetlands is Botany, an electorate held by Christopher Luxon, and from her terrace, Tavola jokes that she’s keeping watch on the border. I ask Tavola — a self-described “anti-capitalist decoloniser”, who lives the tensions of her practice — about her relationship with the mansion on the hill. “The exhibition-making of Vunilagi Vou is an act of divestment from the cultural economy and hierarchy that puts them on top of the hill. I don’t want to climb that hill.” Tavola doesn’t cater or pander to wealthy philanthropists — “I’m not in the business of servicing the necessary re-education of obscenely wealthy people.” It’s a grimly tiring point — I can certainly think of people in the art world, among them philanthropists, in need of education and an adjusted perspective.

Despite curating well-respected exhibition programmes since leading Fresh Gallery Ōtara a decade ago, Tavola comments that “I have never been approached by a philanthropist, not once, and I am very accessible”. Instead, Tavola’s work in and advocacy for Pacific arts has relied on a mix of public funds, commercial sales and small-dollar crowdfunding. The latter has recently been on her mind, and rightly so — crowdfunding has been hailed as a seismic shift in philanthropy. It’s a shift that Jo Blair has also been at the heart of, helping the Arts Foundation launch the arts crowdfunding platform Boosted in 2013. Since then, Boosted has raised $11 million for the arts directly from audiences and communities who want to see projects realised. This is a very different model of philanthropy to the ‘big names on big buildings’ approach, one geared more towards equity of giving. “The $5 gift to a Boosted project is someone jumping on the ladder. That’s the cultural change. [It’s] giving to learn, and being involved in something bigger than yourself,” explains Blair, impassioned about the platform.

Tavola has had a different experience with crowdfunding. In 2022, she posted a video of gratitude that ended with a plea. “It’s hard work to ask for money from our communities like this… Please help us, take the pain away.” The final line was delivered with a laugh, but Tavola’s suffering was real. “I find it so problematic that crowdfunding asks us to go to our people. Especially if you consider that my audience is Pacific people — largely Pacific women — and Pacific women are the lowest-paid sector in this country.” I offer her Blair’s idea that the movement toward crowdfunding is about cultural change: the creation of collective investment in the arts and, perhaps, a whole nation of philanthropists. “It’s nice to think that we could say, ‘My auntie and my random cousin on Facebook could suddenly be my investors’. I think that’s cute. But it also sounds like an idea that rich people would have.”

Reflecting on her last campaign through Boosted Moana, Tavola is at pains to acknowledge the “donations of, like, $7. These are people who are literally saying, ‘That’s what I’ve got to give you right now’.” The process has been very tough. “It just pisses me off, actually. I don’t think any of our donors should be called ‘philanthropists’. They’re mums and dads, everyday people like teachers and kids on Instagram. People who say, ‘I really believe in what you’re doing’.”

Vunilagi Vou is looking elsewhere to sustain its work, including at the Aotearoa Art Fair, a commercially vital marketplace for many of our galleries, based in the Cloud on Queens Wharf. “I actually quite like the Art Fair. It’s basically like a Westfield mall,” laughs Tavola. The gallerist is unperturbed by possible contradictions between ‘Westfield mall’ and ‘anti-capitalist decoloniser’. She knows that her sales pitch will be simple. “You have to care about the fact that Pacific people have a very different existence and life in New Zealand to care about the art. If you don’t care about them, then you’re not going to care about the art.”

NEXT TO THE PVC membrane of the Cloud is another building, one formed of timber and shaped like a suburban state house. At the end of a long wharf, the house looks out to sea — it’s Michael Parekōwhai’s The Lighthouse — Tū Whenua-a-Kura (2017). Parekōwhai’s name had come up throughout my journey, unsurprising for an artist renowned as a ‘master’ of garnering philanthropic support for work in the civic realm. Parekōwhai taught me at art school, and his lessons were usually about confidence and swagger.

The Lighthouse takes the contours of a typical New Zealand state house of the 1950s, a period in which the ‘Big State’ ruled. Parekōwhai’s eulogy to socialised housing contains a three-metre monolith of James Cook, his downcast eyes contemplative in a sea of fluorescent light. It’s grand stuff — a statement of empire through a contested home that probably needs decades to become part of our mythologies in the way that art is uniquely empowered to do. All the more baffling is that The Lighthouse was largely funded by the real estate sector, with Barfoot & Thompson providing an initial million dollars, alongside another million in anonymous donations and $500,000 from Auckland Council.

Response to The Lighthouse in the media was predictably appalled. Amid the furore, more nuanced critiques emerged — some housing activists bemoaned the $2.5 million price tag as grotesque at a time of housing crisis so bad it was labelled a humanitarian issue by the United Nations. I posed this critique to Cundy in the Korean BBQ. He was emphatic: “I want social housing and I want the artwork. I think both those things can be true at the same time — it’s not actually a real choice.” Cundy is right. It’s not a choice we should have to make. Ambitious — and sometimes expensive — art shouldn’t be a luxury we have to defund other things to afford. Nor should we insist that artworks impoverish themselves to the shrinking purses of philanthropy and the state. And insisting on a trade-off between the provision of human rights and the creation of culture is unsettling.

The conditions of The Lighthouse commission have become part of its textual depth, both an act of subterfuge among and a statement of victory over the forces of financialised housing. There is something grand at play here, something like the covert humanism of the Sistine Chapel, funded as it was from the papal purse. The contradictions charge the work, creating a paradox that fuels its journey into the world. In this way, The Lighthouse is a reminder that we’re suspended in a dilemma. Along with the wash of uneasy money, we’re forced into uneasy choices.

People gather at The Lighthouse not only for Parekowhai’s artwork but for the harbour expanse and the views back towards the city. It’s a place where we can see it all — the mess we’re in and the potential to speak through it to tell stories of power and meaning. Resting on the dock, I think back on my journey through the City of Sales, our contested home, and know that questions remain. The glow of The Lighthouse drifts on to the evening waters of the Waitematā and Tavola’s words come to mind. “I choose to live here. I choose the cultural cosmic energy that’s here. It’s profound and special.”

Heidi Brickell (Te Hika o Papauma, Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Rongomaiwahine) arrives to meet me at the water’s edge, her hair charcoal blue like the colours deep beyond the wharf. It feels right to give an artist the final say and Brickell is a bright spark in the visual arts of Tāmaki Makaurau, both in her personal practice and as co-founder of artist advocacy group Arts Makers Aotearoa. “Art is ultimately interesting because it offers novel ways of seeing. If only a small group of people decide what art gets platformed or excluded, we end up with work that reflects a narrow window on the world.”

Brickell weaves in threads so far unmentioned in my journey through the world of philanthropy. “Iwi settlements are a force for diversification, but ultimately, what is needed is a radical redistribution of wealth. It seems to get harder and harder to opt for a life in which time for creating is prioritised over wealth, as everyday survival becomes increasingly precarious for a growing population.” In a society riddled with inequality, perhaps the very act of making art is at risk. Brickell suggests that “focusing too much on philanthropy might miss the point. I think the most urgent issue is giving everyone more space to explore, play and take risks, whatever their medium.” A society without equitable access to creativity is a problem too big for philanthropy to mend. A larger solution will be required.

And there might be other ways. Ways to fund our arts that don’t involve the pearls, dinner parties or gated mansions. There are still places where power is vested not only in assets and capital gains but also in the choices we make together. In the past imagined by The Lighthouse, the state redistributed our wealth, placing it among us. In the actual past, those offerings were never simple, and always riddled with the inequities of colonisation, but the security of homes for many provided a basis for wellbeing in which creativity could flourish.

Art has always been inextricably bound to the resources of its society, and perhaps a true equity can never be achieved. The Alan Gibbs of this world would certainly like us to think so, and when it comes to the state, they take a dim view, believing the whims of private capital to be the higher path. Still, that state offers something that transcends the locked gate and vision of art as private property: an intuitive sense that creativity belongs to us, to the ideas and people that travel through it and called it into being in the first place.

I consider this, the state as potential alternative to the philanthropic purse, while Parekōwhai’s house winks brightly across the water and the last sunlight falls off the Waitematā.

2023-04-08