Mythos and Burritos

The literary world of Giovanni Intra

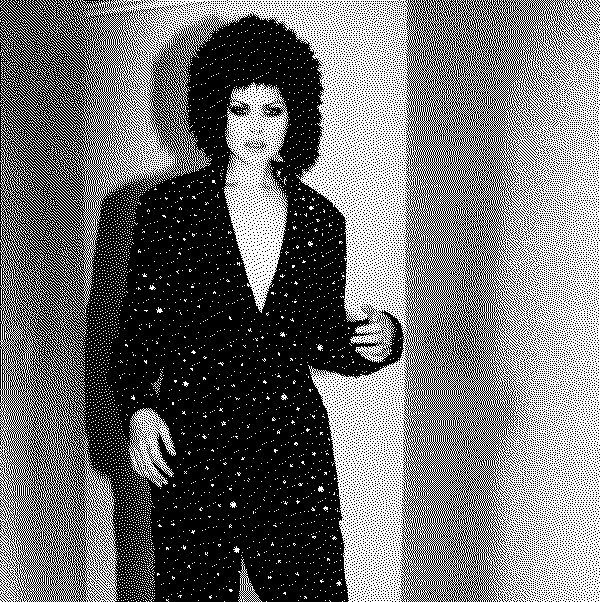

THE YOUNG ARTISTS and would-be gallerists of Tāmaki Makaurau look good: black leather cladding, cheap denim, dangling crucifixes and, most of all, a look of abjection. There is a ghost lurking here among the young, a spiritual godfather whose impact, and mythos, reaches from beyond the grave — Giovanni Intra (1968–2002). The artist, writer and gallerist appears to us anew in the publication Giovanni Intra: Clinic of Phantasms: Writings 1994–2002, a collection that presents the literary output of this prodigious figure.

Legends are formed in the permanence of writing. And those who obtain such a historic status can provide a common style for the zeitgeist. For Intra — who died young, at age of 34 — legendary status is assured, and the last 20 years of incredulous gossip and doting eulogy have sealed it. There are many Intras to choose from, and the multiplicities (and duplicities) of his character charge his legend. Intra the mischievous and charming artist; Intra the writer and critical soothsayer; Intra the influential gallerist and society riler. His short life and long legacy have not been easily assimilated into New Zealand’s love of overseas achievers, and for good reason, as Intra evaded classification and played at a prescient and critically engaged interface of art.

Clinic of Phantasms offers a collection of Intra’s writings spanning eight years — the final years — which saw the artist giddily leave parochial Auckland for Los Angeles, a city to match his hunger and ambition. “Everything you read about Los Angeles is true”, Intra explains, in a statement that could comfortably be applied to the artist himself, as he joyously courted his own reputation. In a city of dream-chasers, Intra was going to make it. A dedicated lover of art whose passion couldn’t be contained, Intra held almost every conceivable role within the art world through his career. In the last decade of life, writing became a key focus of Intra’s output, with the artist reviewing for Artforum and Flash Art, and working as the West Coast editor of Art and Text. These review texts are the core of Clinic of Phantasms and document the literary journey of a person who lived and thought through art.

Intra’s legacy has, since his death, simmered as new devotees of his post-punk irreverence have appeared. The artist-run space he co-founded, Teststrip — “a treehut for the wannabe avante-garde” on Karangahape Rd — has had a sustained influence. His writings, however, have remained obscure, hard to access, and scattered across a plethora of defunct journal archives and hard-drives. Here, Clinic of Phantasms serves an important archival function, rescuing texts from obscurity (and impending loss) and restoring them to public consciousness.

Edited by curator Robert Leonard (a frequent collaborator of Intra’s), the collection begins the journey in 1994, omitting the artist’s ‘juvenilia’. In his introduction to the book, Leonard details its long germination and the shared wish of friends who hoped to renew Intra’s “personal wormhole” of writing. To this end, Leonard enlists friends and colleagues of the deceased artist, with Chris Kraus, Mark von Schlegell and Andrew Berardini providing additional introductions. Kraus (the author of auto-fiction classic and Amazon TV series I Love Dick) is a recurrent presence throughout the collection, appearing in many of Intra’s essays, reviews and think-pieces. Intra had his loyalties — as all cultural critics do — and Clinic of Phantasms traces a set of strong relationships that also includes Tessa Laird, Michael Stevenson and Daniel Malone.

The world of Intra’s writing is bejewelled with friendships, providing a warm heart to an intellect that strives for amorality. Highly influenced by French philosophers of the late 20th century (including Georges Bataille, Paul Virilio and Jean Baudrillard), Intra adopted a suspicious — downright paranoid — view of his Pacific Rim contexts. Drawing upon this intellectual tradition, his writing nonetheless radiates humour and insight — and led by his obsessions, they’re easy reads. Intra inhabited the art world with rare pleasure, and as a writer he cast pronouncements and depreciations with serious glee. As Leonard explains, Intra approached art writing “as an invention, a game”, one that even saw him take occasional liberties with art history — fidelity is always subservient to the story.

Among the gems of Intra’s reviews are Pimps for Chance (1997), a retelling of the ‘philosophical rave’ produced by Kraus in the Nevada desert. Indicative of his sensibility, Intra describes the attending Jean Baudrillard and his wife as ‘French middle-class tourists’ before declaring that the threadbare hedonism in the desert was “worthy of mention in the Old Testament”. He goes on to praise the French philosopher’s “cinematic taste for gambling” and recounts the pronouncement: “‘Isn’t it our endless work, in the absence of God, to reconvert all accident into attraction and seduction?’” Intra’s writing is most intoxicating when he can barely contain himself under varying states of chemical enhancement. His writings, imbued with Gonzo-journeying, frequently return to the deserts of the American west, “a spectacular and crystalline abyss, with endlessness and the possibility of death”.

In the final years of his life, Intra’s writing shifted to a more searching essay form, and these essays offer the clearest insight into his universe. Intra’s perpetually impounded car finds intelligent and hilarious reflection in Too Autopoietic to Drive (2000), while El Gran Burrito!! (2002) offers a takedown on vegetarianism and an intimate survey of Mexican food in the Valley. The essay LA Politics (2002) documents the first years of China Art Objects Galleries and should serve as mandatory reading to any prospective gallerists or artist-run wannabes. Paranoia and Malpractice (2001) is a deep dive into Intra’s fascination with Daniel Paul Schreber, a 19th-century German judge who wrote an account of his own psychosis. It’s all here, the grand and the granular of Intra’s thinking.

While the collection is overflowing, even covering as it does less than a decade of Intra’s literary maturity, something is missing. Intra affirmed the idea that an artist could be many things — including a gallerist and a writer. Clinic of Phantasms speaks to Intra the writer, at the expense of these other ways of being. His artworks deserve their own long-awaited publication (and could potentially have offered an eloquent accompaniment to this collection). Clinic of Phantasms is neatly packaged, a functional resource from which to draw on Intra’s words — but there is still work to be done to know the legacy in full.

The final section of Clinic of Phantasms contains obituaries and tributes by Tessa Laird, Will Bradley and Joel Mesler. These texts offer a poignant — and adoring — portrait of Intra, who, beyond the obvious irreverence, had an open-hearted, ambitious and excitable spirit. Knowing the impending ending, the reader of Clinic of Phantasms might beg Intra to slow down, to get out of the lane that would see him dead in the streets of New York from a drug overdose. It is a tragedy that this exceptional artist and writer died so young, and the intense momentum of Clinic of Phantasms holds bittersweet promise of all the work to come. It was not to be; instead, Giovanni Intra: Clinic of Phantasms: Writings 1994–2002 carries the words of a legend cut short and offers new ground for those who tend his memory.

2023-01-23