Cultural Cringe

Tāmaki Makaurau is obsessed with international art leaders. Has it given up on its own?

“I DON'T THINK we can call it weird anymore,” says Jim Barr in a state of exhaustion. “It’s perverse."

I had asked Barr, a veteran arts observer, to help me understand the appointment of international directors in the nation’s largest art institutions. Complaints about overseas appointments are commonly heard in the art world in Aotearoa, but the issue has different fault lines depending on how one views the problem.

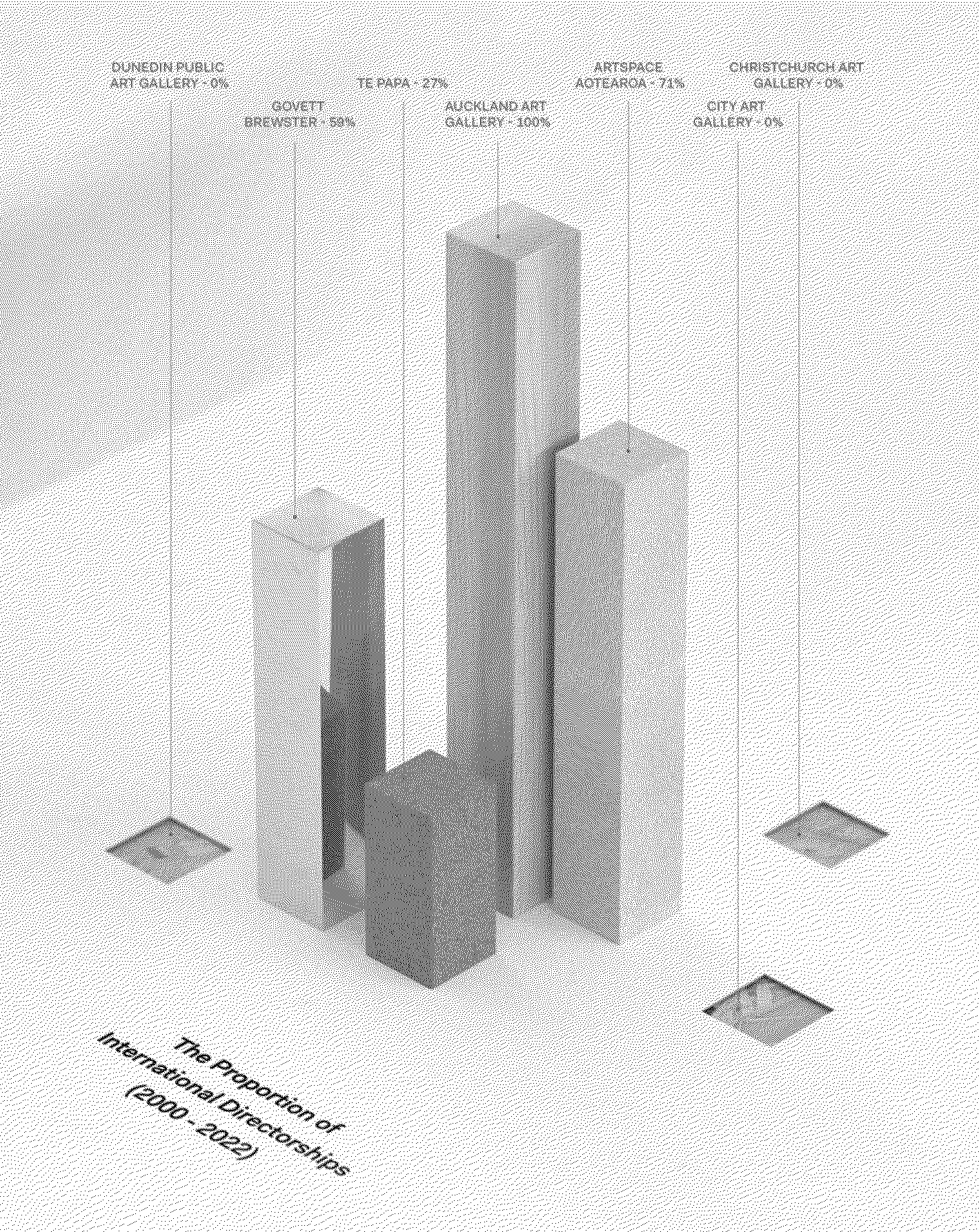

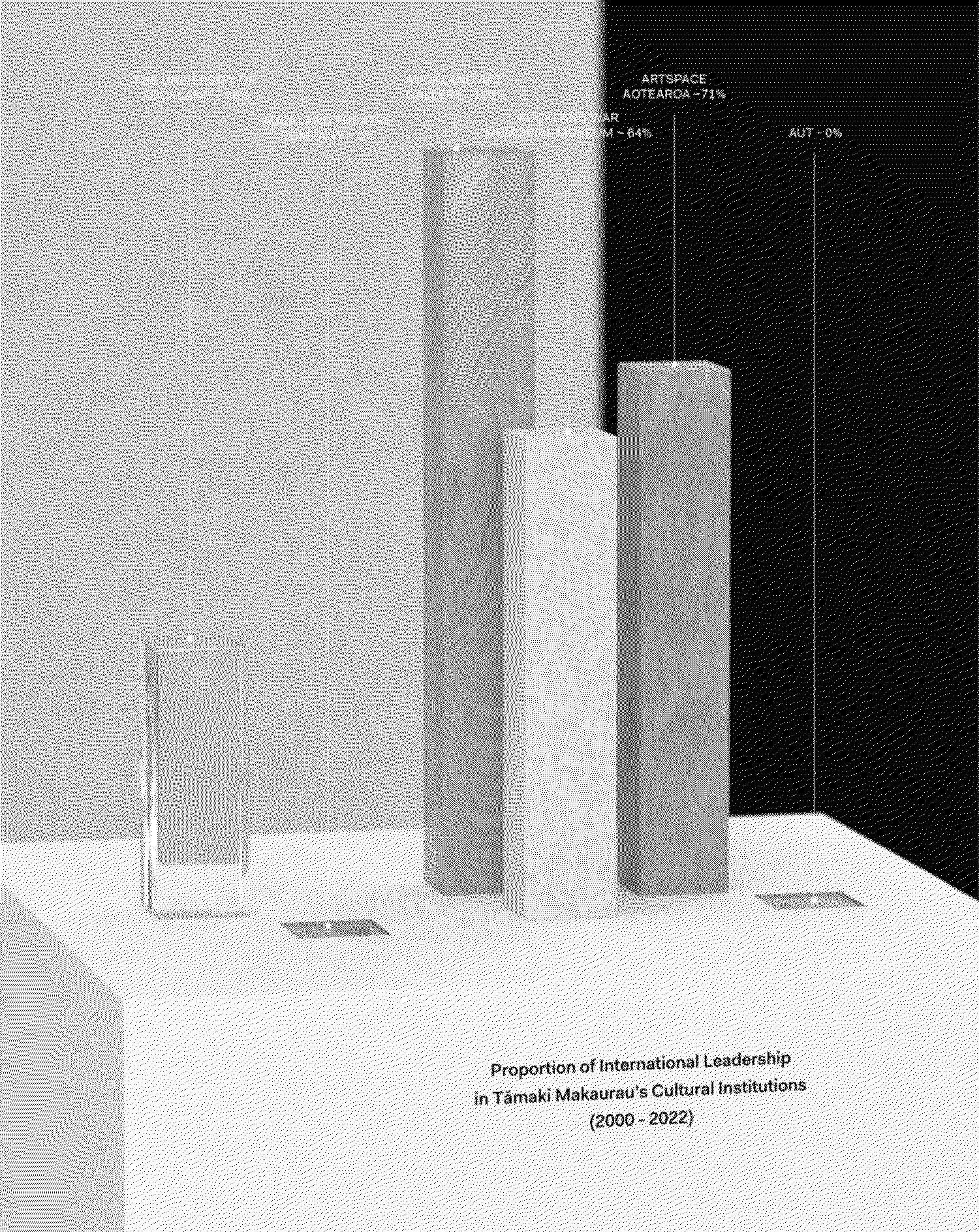

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki has had 11 directors since the gallery professionalised its leadership back in 1952; only two have been New Zealanders — both Pākehā men — and one of these was a temporary appointment. That works out at 18% of the leaders being local. If one calculates the length of time these ‘Kiwis’ administered the gallery, the result is even worse: 14% (rounded down to the nearest whole number) of that 70- year stretch. Barr and I looked at each other, neither quite confident in our maths, but both of us grasping the deeper truth. “It’s even worse than I thought,” groaned Barr.

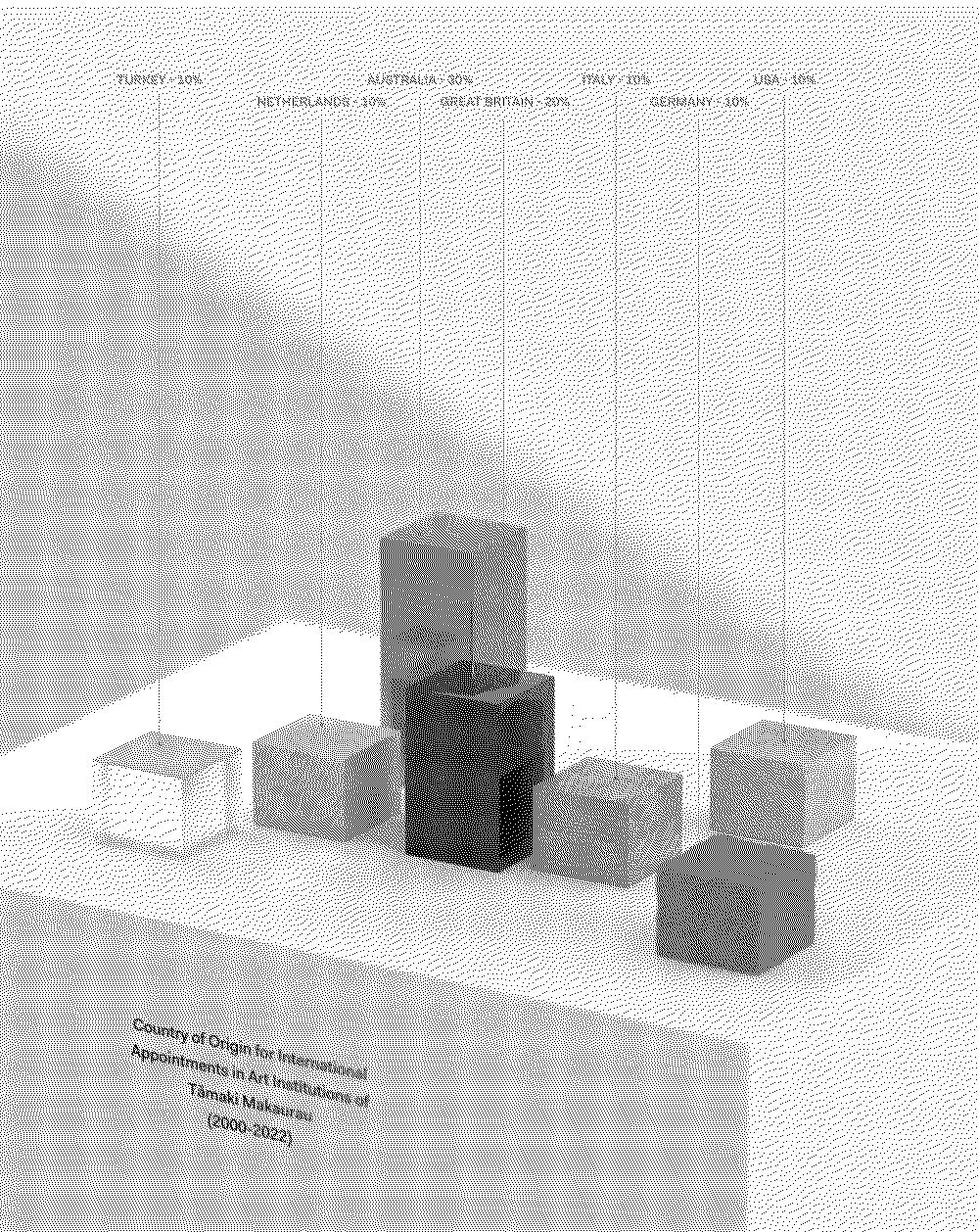

We turned our calculators to Artspace Aotearoa — a smaller institution with an experimental mandate. Ten directors in 35 years, with five of these appointees New Zealanders. That’s 50% — much better. But if you take the institution’s recent history into account, the picture darkens. The last three directors were international appointments, from Italy, Turkey and the Netherlands. A minor issue, perhaps, except for the so-called ‘decolonising methodology’ adopted by the institution, currently being led by a curator from Europe.

ARTSPACE AOTEAROA was founded to — among other things — situate New Zealand art within international contemporary art. Artspace is part of a global discourse arbitrated and dominated by international art fairs, international journals and, most importantly, global museum professionals from an increasingly elite class of cultural workers. If contemporary art did belong to a place, it would probably be the mountain town of Basel in the Swiss Alps — exclusive, privileged and hard to tax.

But Artspace Aotearoa is not in Switzerland; it rests on the ridge known as Karangahape, an important site and thoroughfare in pre-European-contact Tāmaki Makaurau, as it remains today. The institution has struggled to balance contemporary art’s global discourse with the specificities of Aotearoa and its complex histories and knowledges, not least te ao Māori and 300 years of colonisation. In 2019, Artspace New Zealand became Artspace Aotearoa. The name change was one of many decolonising revisions championed by Dutch curator Remco de Blaaij, the current kaitohu/director of the institution, since he arrived in 2017.

In the world of museums, ‘decolonisation’ is on the rise, though its meaning is far from clear. Artist-curator Ema Tavola, the founding manager of Fresh Gallery Ōtara (2006–12), is often asked by Pākehā organisations to speak on decolonisation for the whole Pacific diaspora. Tavola assures me it is not as easy as a “lunch-time workshop”, as “decolonisation in the context of arts institutions is possible only if there is a critical rethinking of power and its provenance”. Tavola is wary of the term being used in the art institutions of Aotearoa, as “to truly commit to decolonisation is to break up the Pākehā power base and rebuild systems that can heal the intergenerational trauma and misinformation of colonialism”. This is something few, if any, institutions are willing to do. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine it ever happening, and many (including the editor of this article) doubt whether it’s possible to ‘decolonise’ these institutions.

I ask — clinging to my topic — How does all this relate to international appointments in our art institutions? Tavola replies: “Who sits in the power seat is the ultimate measure of a decolonial process.” And here’s the rub. While apparently attempting to address issues of colonialism, Artspace Aotearoa imported another leader from Europe.

Caterina Riva (Artspace director, 2012–15) basks in the bright Adriatic light of her office. Despite busily completing an upcoming exhibition, she is keen to speak about Aotearoa, “a place close to [her] heart”. She remains optimistic about international directors at Artspace, explaining, “as an outsider, especially at the beginning of your tenure, you can see more opportunities for things to happen than the local community”. I was curious about what she could see that local eyes could not. Alluding to the sectarian nature of the art scene, Riva says she made a deliberate effort not to “pay too much attention to the rumours”. I felt she had a point, as small art scenes are riddled with established hierarchies. In this regard, an outside arbiter is appealing.

Speaking to Riva, I sensed some misgivings about the structure of Artspace, particularly the length of the director’s fixed term — first three years, now four. “You start getting the ropes when you are halfway through your term.” This felt understandable, as getting used to a new job — let alone a country — takes time. How long would it take for a local appointment to ‘get the ropes’, I wondered. If we appoint only international directors, what proportion of our programming is still trying to orient itself?

“It’s a lot to expect of someone to arrive from overseas (and it’s typically from Europe), gain fluency in the cultural conversation here and deliver an impactful, internationally engaged programme in three years,” says Sarah Hopkinson, a gallerist who’s seen the international appointments come and go.

I looked at the next on the list of Artspace’s recent international directors, Adnan Misal Yıldız (2015–17), who became a legendary local presence during his tenure. Speaking from bed after receiving a vaccine, Yıldız spoke about the tension of international appointments, asking, “How will a blind date work?”

Yıldız, a self-described “queer man from Anatolia”, represents another world to the one he joined on Karangahape Rd, though he does feel that his journey shares in some of the forces that have shaped Aotearoa. “Turkey has its own unspoken history of colonialism, and I wouldn’t have survived there without my politics”.

Despite his reputation for high drama, Yıldız’s tenure is remembered warmly by many, including Barr. “I had a terrible relationship with Adnan, but I so admired him. Adnan was the classic example of an overseas appointment which really worked,” he says. I felt similarly about Yıldız. He had both a curiosity and an indifference towards the intricacies of Aotearoa and embarked on bold work here, creating platforms for queer communities who had often been omitted from Aotearoa’s cultural conversation. There was a frenzied and dynamic pace at Artspace during his three-year term, with a sense of ‘new life’.

Reflecting on the institution and its preference for international directors, Yıldız spoke with his usual candour. “I was broken-hearted to leave with a white Dutch dude [de Blaaij] arriving … A lot of good candidates had applied, including Māori and Pasifika women who could have led the decolonising work within the institution.” Yıldız had the sense of someone who was speaking a retrospective truth. “I was disappointed, but remained silent to allow the new director’s programme to unfold.”

I needed to speak to the much-maligned de Blaaij, who — so said Barr — was “not entirely to blame for the predicament he found himself in”.

Remco de Blaaij (2017–22) speaks from the new ground-floor premises of Artspace Aotearoa — another revision that took place in his tenure, one designed to increase accessibility for visitors. He starts with the disclaimer that debates around international appointments are “mostly taking place from emotion, and not necessarily based on real figures”. Fair enough. There is a ‘culture of grievance’, and locals often become impassioned about appointments and forget the data. De Blaaij has his own feelings on the matter: “We need to look more long term. For a long time, the arts wanted to pick the fruits from engaging with communities, but not ‘pay the price’ for it.” Thoughtful and calm amid a conversation that implicated him, de Blaaij reflected that “the times of star curators in that sense are also slowly disappearing. We need to rethink our obsession with leadership and being at the top.”

I bring up the d-word. De Blaaij replies: “I hope a decolonial methodology is clear from the actions and elements we delivered in Artspace’s programme. We have not succeeded at all, but we hopefully have shown some steps in the right direction.” I ask de Blaaij about the tension between efforts to decolonise and institutional leadership from Europe. His answer is forthright: “I sympathise with it fully. It is a time and place for stepping back and empowering other voices. There are positions that I can simply not speak from.”

I repeat the words often spoken to me, a white man: Do white people need to start leaving the room? De Blaaij pauses thoughtfully, his answer unequivocal: “Yes, full stop. Step away, leave the room. Help in other ways.”

Directors do not appoint themselves. There are governing bodies that provide institutions with continuity of vision and, crucially, appoint new directors. Artspace Aotearoa has a tiaki/board of trustees who are entrusted with this task. Hopkinson reflects on the board that has produced 10 years of international appointments. “In the recent history of Artspace — including for the period in which the current director was appointed — I think there have been some real issues with the make-up of the board; it doesn’t feel connected to the Artspace audience.” I ask Hopkinson to elaborate, and she puts it plainly: “Too old, too white.”

Artspace has responded to this issue with seven new tiaki appointments under the leadership of kaihautū (chairperson) Desna Whaanga-Schollum (Rongomaiwahine, Kahungunu, Pāhauwera, Ngāi Tahu Matawhaiti). The appointments have seen a significant shift towards greater presence of tangata whenua (now 44% of the board), as well as voices with a research focus on decolonisation and inclusion. Speaking from her iwi territories of Rongomaiwahine, Kahungunu & Pahauwera in Te Matau-a-Māui (Hawke’s Bay) where she now resides, Whaanga-Schollum is busy working towards the appointment of a new kaitohu for Artspace.

She has a framework for the complex conversations ahead. “As tangata whenua, I don’t feel the need to constantly orient myself towards decolonisation, because if I was to do so, I would always be defining and reflecting on my identity from a point of deficit. Decolonisation is not how I know my identity; it is a structural issue for a number of generations, but it is not my identity. Te ao Māori is a position of awareness, strength, of knowing, and of being.”

Reflecting on the changes made at Artspace during de Blaaij’s directorship, Whaanga-Schollum offers a clue to the upcoming appointment. “We do feel that we are at the point that we can put the tono forward for a tangata whenua kaitohu. There have been significant structural changes, in terms of who decides what the objectives are, who holds responsibility and authority … Artspace is also very clear that it is really the start of a much longer journey, which we would hope provides fertile opportunity to dig deeper into the knowledges of here.”

Well aware of the criticism arts institutions and their appointments can attract, Whaanga-Schollum reflects that “trying to keep our values and longer-term goals front and centre of every conversation can be challenging in a world that seems obsessed with the immediate moment … I can see our thought systems and latent creative potential getting distracted by a kind of chronic short-termism. When we are stuck in that reactive, survival mode, it’s pretty hard to conceptualise a different way of doing things.”

I wondered for a moment if the successive international appointments helped to perpetuate this ‘short-termism’, then thought back to the 34 years of international appointments at Auckland Art Gallery.

Whaanga-Schollum was generous and thorough in her kōrero, and provided an important challenge to my previous advocacy for ‘local appointments’ — an imprecise phrase with altogether different resonances for tangata whenua. Speaking to her, I was reminded of Tavola’s earlier words to me: “Pākehā need to learn how to sit with their discomfort, support each other to unlearn the ways Pākehā have shaped knowledge and perception of otherness.” Unpacking discomfort is important for Pākehā if there is to be meaningful engagement with decolonial processes, at the level of the institution and the individual.

Speaking to members of the arts community in Tāmaki Makaurau about Artspace, there’s a sense of sympathy and frustration for its challenges and, in particular, around the role of kaitohu. “I wouldn’t want the job” or “better them than me” are common refrains; a sense of intimidation is generally acknowledged. Vera Mey, a curator and the interim director of Te Tuhi, knows the feeling. “In mid-sized institutions such as Artspace, the expectations on leadership feel so demanding. That person must simultaneously be many things at once: an international interlocutor, a local mouthpiece, curatorial visionary, community facilitator and quasi reformer of past omissions within the local arts community.”

All this is a lot to expect of someone, no matter where they come from.

AUCKLAND ART GALLERY Toi o Tāmaki is older than Artspace and is more directly interwoven with a colonial history of erasure and dispossession. The gallery rests on the site of the Albert Barracks — the lower redoubt wall would have passed through its Grey Gallery. That part of the building is still named after Governor George Grey, a founding benefactor of the gallery who was responsible for the invasion of the Waikato and confiscation of 1.2 million hectares of Māori land. When the gallery opened on a late summer day in 1888, the gilded frames of Europe went immediately on display, reflecting the belief that ‘high art’ could not be made in the colonies, by either Māori or Pākehā.

Since then, the gallery has come a long way — just not far enough.

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki owns the country’s largest permanent collection of New Zealand art, and its directorship is, along with Te Papa, one of our top arts appointments. One might hope that the directorship might occasionally be given to bright stars of Aotearoa. Nope — the last local Pākehā figure to lead here completed their tenure in 1988.

Following a $121 million redevelopment seen through by its Australian director Chris Saines, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki reopened in 2011 with a new stress on its reo name and a renewed commitment to the bicultural principle enshrined in Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Visitors could see this in the representation of Māori art, the architectural incorporation of Māori iconography, te reo wayfinding and literature, and observance of tikanga during formal events. When Saines stepped down, however, two further Australian directors were appointed. An attempt in 2019 to appoint a New Zealander, Gregory Burke, went astray — he withdrew his application after being accused of workplace harassment at his previous job in Canada.

In 2020, the promise of bicultural partnership seemed newly honoured with the landmark exhibition Toi Tū Toi Ora, curated by curator Māori art Nigel Borell (Pirirākau, Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Te Whakatōhea). Seen in a broader context, this was the first significant survey of Māori art at the gallery since Pūrangiaho: Seeing Clearly (2001) — a nearly 20-year lapse that local leadership should have sought to address earlier.

Toi Tū Toi Ora was a moment of renewal at the gallery and expressed a hope that Māori artists would no longer be understood through eurocentric curatorial framing but rather within the meanings of te ao Māori. The show itself was a triumph, though the immediate resignation of Borell, citing the lack of autonomy for Māori leadership, complicated matters. His experience with Toi Tū Toi Ora became instructive of the nature of biculturalism within the institution and ultimately raised hard questions about the appointment of international directors. In an act that struck many as courageous, Borell went on the record with Joanna Wane in Canvas: “It’s time for New Zealand institutions to be ‘brave enough’ to vet international applicants for cultural competency, including an understanding of the Treaty of Waitangi and New Zealand history.”

Speaking to Borell now, the challenge of those years at Auckland Art Gallery seems to have passed. He is relaxed as he reflects on Toi Tū Toi Ora. “When we are allowed to tell the story ourselves, we can have glorious moments of change,” he says. Visitors shared this sentiment, with well over 6000 people visiting the exhibition in its opening weekend, marking a record for the gallery. Tavola observed the tension of the moment and knows that “a phenomenal show was produced in that climate, but not because of the institution. It was produced because people like Borell love a good fight and know that their communities have their back.”

Reflecting on his broader responsibilities as Māori curator, Borell raises a daily tension. “Māori do the heavy lifting of the bicultural relationship, and as curator Māori art, there’s a lot of invisible work that is incredibly sapping.” I pose a hypothetical to him: Could he imagine a Māori director being appointed to the gallery one day? His response is nuanced: “A Māori director would have double the scrutiny on them, and that isn’t necessarily the answer. A good director can empower Māori voices and would know how to share power and leadership.”

Jasmine Te Hira (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Atiu, England) worked alongside Borell at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and held a range of educational and public programming roles between 2016 and 2020. Te Hira is clear about the challenges faced by international appointees and highlights the responsibility of advisory roles in “transitioning [foreign appointees] as manuhiri here into Aotearoa”. This process must include developing an awareness of “the complexities of Aotearoa New Zealand histories and Te Tiriti responsibilities”. This echoed my own feelings, which did include some sympathy for the international incomers. How can we expect these people to properly embody Te Tiriti within our cultural institutions when many New Zealanders struggle to grasp the meaning and implication for themselves?

“Art institutions can play a role in advancing the critical consciousness of Aotearoa — how we name, locate our world in relationship to our past, present and futures,” Te Hira says. “If we seek to have world-leading arts leadership here in Aotearoa that binds relationships between taonga, histories, people, and land, let’s appoint culturally intelligent, place-based, mana-enhancing leadership … Art institutions have a place in the lived realities of taonga. Our access to these taonga and their active material meaning in our lived realities can shape the relationship and understanding of a generation’s sense of self.”

Barr puts it more starkly: “If they were serious about decolonisation — which they aren’t — let tangata whenua have the complete control of the museum for 10 years and see what happens.”

The appointment of directors at Auckland Art Gallery ultimately comes down to a selection panel of unnamed members, overseen by Auckland Unlimited (formerly Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development and Regional Facilities Auckland). The gallery is managed by Auckland Unlimited, with the director serving its board (and, by proxy, the residents of Tāmaki Makaurau). The 10-person board of Auckland Unlimited appears to be made up of mostly white business leaders, with one member holding cultural industry expertise and two tangata whenua members (one of whom joined in 2021).

I approached Auckland Unlimited for comment, asking if they could expand on the organisation’s rationale for leadership appointments within the Auckland Art Gallery, and whether the low proportion of local appointments is perceived to be an issue. I received the following statement, attributed to Auckland Unlimited chief executive Nick Hill:

"Auckland Unlimited and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki are part of the important conversations happening across Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and Aotearoa New Zealand to address the cultural biases inherent in legacy organisational structures and systems. The cultural sector in particular has a vital role to play in leading the way to ensure Te Tiriti principles are woven through our work, as well as in our governance."

Hill’s statement then highlighted the “opportunity to embed Māori outcomes throughout our organisation and in the way we deliver for Auckland”, before detailing recent Māori appointments at the board level and within Auckland Art Gallery, including the creation of a new leadership role within the gallery, head of kaupapa Māori. All of this, plus a commitment “to learning from the past” for the future of the city, is conveniently outlined in Te Mahere Aronga Māori, Auckland Unlimited’s Māori Responsiveness Plan.

I was grateful for the response and could see that changes had been made within the gallery since Toi Tū Toi Ora, though reading the written statement, I struggled to feel the presence of the chief executive and missed the all-important ‘discomfort’ Tavola told me to seek out. The correspondence with the communications teams was warm and efficient, but my question remained unanswered. I still didn’t know why Australians had led the gallery since 1996, nor whether this was perceived as an issue within the institution.

I had hoped to speak to Kirsten Lacy, the Australian director of Auckland Art Gallery since 2019, but was politely referred back to Auckland Unlimited.

I TRY AGAIN to see the problem from Auckland Unlimited’s perspective. Who should have been on the bench of possible New Zealand directors after the abortive effort to appoint Burke? There could simply be a lack of local expertise. I put this to Barr, who pauses for a moment before producing a list of six local high-level institutional curators who would have been well qualified to lead Auckland Art Gallery between 1988 and 2020. I look at Barr’s list of candidates, some of whom, he claims, applied for the position more than once. The list is impressive, and each of the named curators is at least the equal in expertise of the incoming Australians. There’s nothing in the LinkedIn accounts of the Australian appointees that is beyond local expertise: a master’s in art history, curation or even business administration, followed by successful leadership of a medium-sized art institution or biennale. This is a well-trodden path, one that can be catered for within the pacific region of Aotearoa.

For further perspective, I wanted to speak to a bright star working outside of large art institutions. Vera Mey has worked in Aotearoa, Asia and Europe and knows the tensions for creative workers here. “I’m part of a newer generation of cultural workers in Aotearoa who are no longer attracted to the conventional ascendance to leader- ship that was once forged,” she says. Mey — one of many with the requisite experience for leadership — then raises a deeper issue: “We want arts organisations to match our political values around equality and are impatient at how slow institutions can be … Rather than tilling away in the hope of the promotion lottery, I see cultural workers making things happen for themselves, setting up new institutions and desiring actual political change through action from within.”

I THINK BACK to that mountain town in Switzerland. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki has placed itself on a circuit of international appointments, drawing upon increasingly elite, globalised and corporate-minded leadership that is structurally inattentive to place. This leadership presides over an art museum that functions commercially as civic entertainment, a shift exemplified by the rise of ‘block- buster’ exhibitions and on-site events. White people are primed to succeed on this circuit of leadership appointments; their privilege in education, ease within global institutions and, crucially, networks of influence provide them greater access to corridors of power.

The position of Aotearoa’s art institutions in the wider world is an enduring tension. In Mey’s view, “larger institutions have an embedded local position but need to speak to a broader global context, which is difficult with- out international experience or even a broader regional outlook”. Cultural workers like Mey come with a breadth of international experience, opportunities that are often supported by funding bodies at home. This raises hard questions about resource allocation. We spend a lot of money ensuring our creative workers are at the forefront of international practice, only to turn around and not give them the top jobs at home.

I ask Mey if persistent international appointments are leading to a brain drain? She finds nuance in my blunt question. “I understand why people leave to test themselves out in foreign contexts. There’s a heaviness in the current cultural-political climate where, due to the small number of institutions, we see what exists as the be-all and end-all. Scrutiny of cultural activity has intensified with social media, and there’s more reluctance with experimentation at the risk of getting it wrong. I can understand why cultural workers might want to be in an environment where they have a healthy critical distance and where experimentation might be a little more forgiving.”

This is the art scene that Aotearoa is burdened and blessed with. We’re critically rigorous, uncompromising (on our own most of all) and sometimes forget the all-important compassion.

AS I SPEAK to the arts community of Tāmaki Makaurau, other pressing and structural issues emerge. For recently returned local curator Tendai Mutambu, issues of institutional leadership should be grounded in a broader struggle: “a conversation on directorships is not the most urgent issue for me”. Instead, Mutambu points towards his involvement in Dignity and Money Now (aka DAMN), an advocacy group and campaign for more liveable lives for culture-sector workers in Aotearoa. “Conversations about individual directors feel like cult-of-personality-lite masquerading as worthwhile discussions on power. Some exalted import is not going to do the work of figuring out for us what kind of [art] world we want or need — that is, a more equitable one. A local director might not either, but they’re better placed to understand the stakes and the context.”

I took Mutambu’s point; a fixation on leadership can indeed obscure broader disparities. There is more to con- sider than who sits in the director’s chair. The presence of nefarious philanthropic influence, the corporatisation of public institutions and a complicity in the values of the art market — all these exert powerful structural influence. Each deserves its own careful analysis, as each leaves its own troubling imprint on our art institutions.

Art institutions mirror the tensions of broader society and belong to a world suspended between truth and power. The condition of truth is important, and good art will always demand it. Decolonisation — possible or not — plants a hard truth at the centre of our art institutions. Artspace Aotearoa is grappling with this tension and seems poised for change, while Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki appears adrift in a continuous stream of Australian appointments that keep us looking outward. Pākehā discomfort (particularly at the executive level) is a prerequisite for meaningful engagement with the ongoing effects of colonialism, and as de Blaaij has concluded, white people need to start leaving the room to make space for others.

Leadership is key to imagining new paths through this fraught terrain, and the leader sets the vision and limits of the institution. Tāmaki Makaurau is filled with cultural workers willing to imagine other ways of honouring ourselves, and they consistently meet institutions unwilling to empower them. As Borell reminds us, appointing tangata whenua is not necessarily the answer — empowering leaders with a deep and embodied understanding of Aotearoa and Te Tiriti is. That means looking within and finding those among us who can help articulate who we are, and who we can be.

2022-07-01